-

current

recommendations- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

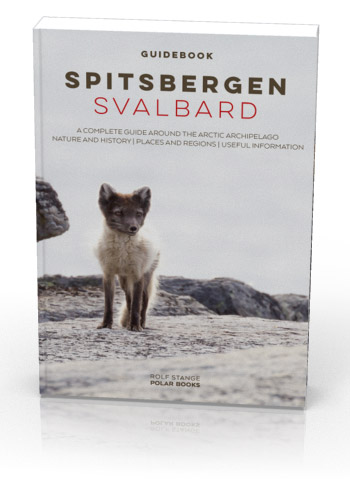

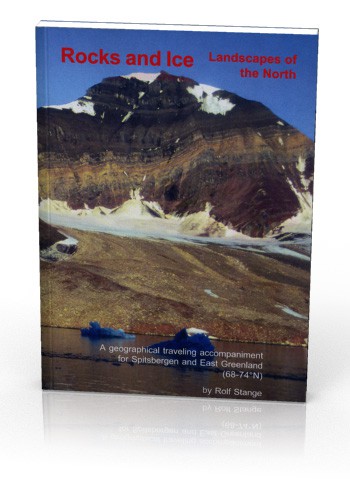

- New Spitsbergen guidebook

The new edition of my Spitsbergen guidebook is out and available now!

- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

Page Structure

-

Spitsbergen-News

- Select Month

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- November 2009

- October 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- April 2000

- Select Month

-

weather information

| Guidebook: Spitsbergen-Svalbard |

Bohemanflya

Wide tundra and early mining in Isfjord

Bohemanflya is an extensive plain on the north side of Isfjord.

Extensive plains (Norwegian: flya, pronounced something close to ‘fleea’) are a typical phenomenon of many coastal areas of Svalbard. Bohemanflya is one of the largest of these plains. It lies in the middle of Isfjord, between the bays of Borebukta and Nordfjord, less than 30 kilometres northwest of Longyearbyen. Because it is so flat, it is hardly noticeable from afar, at least from sea level.

Bohemanflya from Nordenskiöldfjellet near Longyearbyen, seen from a distance of 28 kilometres. In the foreground to the right is Bohemanneset.

From close up, however, you get a very varied and interesting impression of the tundra, wildlife and history of Spitsbergen, and the landscape from the coast to the many details of the tundra also has a lot to offer.

Coastal and tundra landscape in the south of Bohemanflya.

Despite the relative proximity to Longyearbyen, it is not necessarily easy to get really close to this landscape: the coastal waters are mostly very shallow and poorly protected, so that landings are by no means possible everywhere and only in good weather, at least in the south-eastern part of Bohemanflya, which is very exposed in the large Isfjord. The outermost point in this area, Bohemanneset, is a very beautiful and interesting corner.

Bohemanneset is a narrow headland at the south-eastern point of Bohemanflya.

Bohemanflya is part of the Northern Isfjord National Park. On the south side is the Boheman Fuglereservat, a strictly protected area where you have to stay at least 300 metres away from the islands between 15 May and 15 August. It is actually so shallow that you will do most likely so anyway. However, non-motorised boats (especially kayaks) are allowed to pass north of the islets in the reserve, although you must pass through the area as far away from the islets as possible.

Geology

The geology is particularly interesting at Bohemanneset and the old mining settlement of Rijpsburg. Sandstone from the Lower Cretaceous period, i.e. over 100 million years old, can be found in this area. This light-coloured, coarse-grained sandstone was deposited in river deltas that rapidly advanced into the shallow shelf sea and is known locally to geologists as ‘Festningen Sandstone’, after a small island to the west of Grønfjord. This is worth mentioning because the Festningen sandstone can be found in many places in Spitsbergen and is often striking in terms of landscape and geology, for example at Kvalvågen on the east coast, where footprints of iguanodons (dinosaurs, 7-8 metres tall) have been found in this very sandstone, as well as at Festningen in Isfjord. Footprints from these sites are on display at the museum in Longyearbyen and at the Natural History Museum in Oslo.

Lower Cretaceous Festningen sandstone and underlying coal layer at Bohemanneset.

No dinosaur footprints are known from Bohemaneset, but what the vegetarian iguanodons lived on has survived in another form: The vegetation of the coastal marshes has become coal, which is clearly visible at both Bohemanneset and Rijpsburg.

Further west and north, the Bohemanflya consists of older sedimentary rocks from the Mesozoic, Jurassic and Triassic periods to be a bit more precise.

Jurassic sedimentary layers in Øienbukta.

Landscape

The most striking landscape feature of Bohemanflya is the very extensive flat plain itself. To the north of the Bohemaneset, a gentle hill rises to an altitude of 67 metres, and the plain gradually rises towards the mountains to the north. In between is a vast expanse of flat tundra with wetlands, small streams and a few small lakes.

Tundra. A September day in Spitsbergen can be so beautiful!

The shores of the neighbouring bays of Borebukta and Yoldiabukta are covered by wide moraine ridges.

The water near the shores is very shallow, especially in the south and east, so even small boats have to be careful and can not always and everywhere reach the shore. Here, the lowlands simply continue underwater into Isfjord.

Flora and fauna

Bohemanflya is covered by extensive tundra over a large area, and there are always beautiful and interesting types of vegetation, ranging from wetlands to salt-dominated communities near the shore.

A beautiful specimen of moss campion at Bohemanneset.

In some places, there are many beautiful flowers in summer, and sometimes a rare species such as Mertensia, a salt-tolerant species that grows near the beach.

Polar cress.

Of course, reindeer are not uncommon in such a landscape, and arctic foxes also roam around trying to catch one of the many birds: There are geese foraging on the tundra, king eiders and red-throated divers around the small lakes, purple sandpipers on the shore and common eider ducks breeding on the offshore islands, to name but a few.

Arctic fox, here the dark version (“blue fox”).

History

To the west of Bohemanneset lies Rijpsburg, a very interesting piece of Spitsbergen history: The Norwegian captain, seal hunter and adventurer Søren Zachariassen mined several hundred kilos of coal here in 1898. Others had done this in various parts of Isfjord before him, but Zachariassen did it not for his own use, but with the idea of taking the coal to Tromsø and selling it there. He is therefore considered to be the first person to engage in what you might thus call commercial mining on Spitsbergen, although both ‘commercial’ and ‘mining’ are big words when it comes to what Zachariassen did. Nevertheless, Søren Zachariassen deserves the honour of having kind of started the very formative era of mining on Spitsbergen. Others soon followed, and in the years that followed, all the settlements on Spitsbergen were founded as a result of mining.

The hut at Rijpsburg where Johansen and Lerner spent the winter.

The name “Rijpsburg” came some years later during the Dutch period.

Until then, the place was known as “Bohemanneset” or “Cape Boheman”.

Hjalmar Johansen and Theodor Lerner spent the winter of 1907-08 in the hut at Bohemanneset (actually a good 2 kilometres west of the headland). Both are well-known figures in polar history: Johansen accompanied Fridtjof Nansen on the Fram in 1893-96 and also on the famous attempt to reach the North Pole on skis, including the subsequent winter on Franz Josef Land. Theodor Lerner, a Frankfurt journalist, adventurer and Spitsbergen traveller, undertook numerous expeditions to Spitsbergen and became famous in the small world of Spitsbergen as the ‘Prince of Fog’, mainly for his attempt to take possession of Bear Island for himself, but also for his emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm II.

Old mine shaft west of Rijpsburg. The exact age is unknown.

This picture was taken from outside. Never try to enter an old coal mine,

it may well turn out to be a death trap!

Later, a Dutch company, the Nederlandse Spitsbergen Compagnie (NeSpiCo for short), took over the rights to the coal fields on Bohemanflya and in ‘Green Harbour’ (Grønfjord). The company began mining at both sites, naming them after the heroes of the Dutch expedition that discovered Spitsbergen in 1596. Rijpsburg (named after Captain Jan Cornelis Rijp) was soon abandoned, however, as the coal deposits were not sufficiently profitable and the shallow waters made it impossible to ship coal in any quantities.

There is a special page on Rijpsburg (click here).

The second place was Barentsburg, which is known to still exist. Barentsburg and Rijpsburg passed into Russian hands in the early 1930s.

Russian claim sign from 1970.

Later the whole area was declared a national park, making mining impossible.

In 1925-26, another trapper spent the winter in Rijpsburg, the Norwegian Arne Olsen, who died of scurvy in April 1926 after a lonely winter – the last to die on Spitsbergen. His grave is in Longyearbyen cemetery.

Just north of Rijpsburg are the remains of an old grave under some boulders. The man buried there is probably a Pomor from the 18th or early 19th century; the remains of a Russian Orthodox burial cross used to be there.

Pomor grave near Rijpsburg.

Photo gallery: Bohemanflya

Some impressions of the beautiful landscape and nature.

- gallery anchor link: #gallery_3523

Click on thumbnail to open an enlarged version of the specific photo.

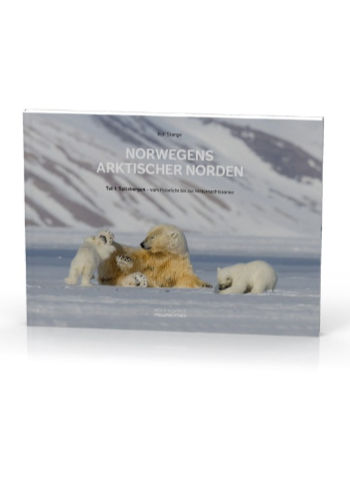

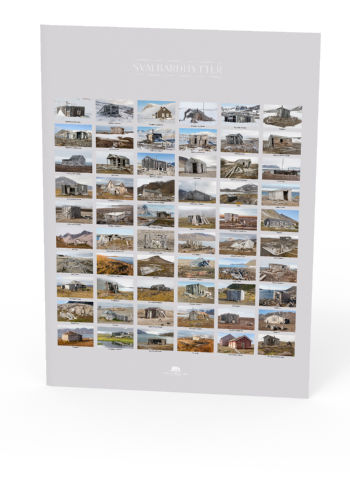

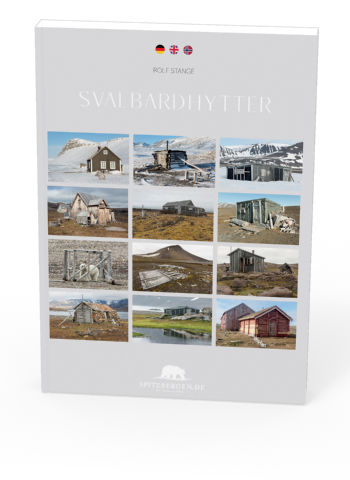

BOOKS, CALENDAR, POSTCARDS AND MORE

This and other publishing products of the Spitsbergen publishing house in the Spitsbergen-Shop.

last modification: 2025-02-10 ·

copyright: Rolf Stange