-

current

recommendations- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

- New Spitsbergen guidebook

The new edition of my Spitsbergen guidebook is out and available now!

- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

Page Structure

-

Spitsbergen-News

- Select Month

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- November 2009

- October 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- April 2000

- Select Month

-

weather information

| Guidebook: Spitsbergen-Svalbard |

Home → April, 2025

Monthly Archives: April 2025 − News & Stories

New population statistics for Spitsbergen

Statistics Norway (Statistisk Sentralbyrå) recently published new figures on the population of Svalbard. According to these figures, 2556 people were officially living in the Norwegian settlements (Longyearbyen, Ny-Ålesund) on 1 January 2025, a decrease of 61 people compared to the previous year’s figures.

The Norwegian government will hardly be pleased that Norwegians are over-represented among those who have left: A full 50 out of 61 (around 82%) have a Norwegian passport. According to the latest figures, the population in Longyearbyen and Ny-Ålesund, totalling 2556 people, includes 1626 Norwegians (63.6 %). And the Norwegian share of the population is likely to decrease even further when mine 7, the last Norwegian coal mine in Spitsbergen, closes in the summer, as Norwegians are also disproportionately represented among the miners. The government will not be happy with this, as a higher proportion of Norwegians on Svalbard is an explicit political goal.

There were officially 2556 people living in Longyearbyen and Ny-Ålesund on 1 January 2025.

An interesting development can also be seen in the non-Norwegian population: while Thais (currently 113) were in second place after Norwegians for many years, they have now been overtaken by Filipinos (127). In fourth place are Germans (94) and in fifth place Russians (67).

Speaking of Russians: 297 people lived in Barentsburg and Pyramiden in January, the lowest number since population statistics began in 2013. Among these 297 are also a number of Ukrainians.

There were officially 2556 people living in Longyearbyen and Ny-Ålesund on 1 January 2025

US tariffs on exports from Svalbard and Jan Mayen

The news of mine 7’s future as a museum was an April Fool’s joke (and clearly recognisable as such, I hope, isn’t it?) – this probably sounds like an even more absurd April Fool’s joke, but it’s not: the tariffs that the US government is said to have introduced also affect Svalbard and Jan Mayen.

But not because they automatically fall under the tariffs because they belong to Norway, but because they have their own tariffs. While Norway is subject to a 15% tariff, exports from Svalbard and Jan Mayen to the US are subject to a 10% tariff, according to NRK.

The good news is that, compared to many other countries, the export economy in Longyearbyen and Olonkinbyen (the station on Jan Mayen) gets off relatively lightly.

There is simply no export economy in these or other places on the islands. Svalbard’s only export so far has been coal, which has not been sold to the US in recent history. And there is no civilian population on Jan Mayen anyway, just a station, and therefore no economy at all.

On Jan Mayen there is just as much export economy as you can see in this picture: none at all.

Svalbard and Jan Mayen are not the only remote islands without an export economy that the US government has imposed tariffs on. According to Spiegel online, they include the sub-Antarctic islands of Heard and McDonald, as well as Norfolk Island near Australia.

Comment

If anyone has an explanation as to why this might make sense (leaving aside the fundamental sense or nonsense of tariffs), I would be interested to hear it. I have no idea.

To Dunérbukta and Elveneset. And this and that.

Just a few impressions of the beautiful arctic winter, without many words.

A trip to Dunérbukta on the east coast. Icy cold, about -25 degrees. And a little reminder of why you should always have a shovel with you in the snow (the second reason being the danger of avalanches, of course).

- gallery anchor link: #gallery_3584

Click on thumbnail to open an enlarged version of the specific photo.

And another trip to beautiful Elveneset in Sassenfjord. You don’t always have to go far…

- gallery anchor link: #gallery_3587

Click on thumbnail to open an enlarged version of the specific photo.

Make this page nicer

And more news from the ‘Make this page nicer’ section:

- Faksevågen in Lomfjord: the beautiful mountain hike on the edge of Hinlopen Strait.

- Hingstsletta, also in Lomfjord. It used to be a polar bear paradise a while ago, as the pictures will show.

- Sigridholmen, a little pearl of nature in Kongsfjord.

And what else

And what else? Oh yes, the stocks are being replenished. The entire selection of Svalbard kitchen slats from Longyearbyen is now back in stock.

Kitchen boards from Longyearbyen:

now all available again in the spitsbergen-svalbard.com shop 🙂

A new future for mine 7?

Just last week, the closure of mine 7, Norway’s last coal mine on Spitsbergen, which was originally planned for next summer, was the subject of discussion not only in Longyearbyen, but also in political circles in Oslo.

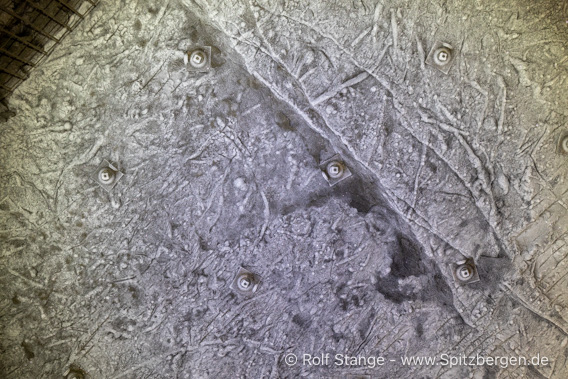

After geologists recently discovered the footprints of a pantodon in the mine, the authorities reacted quickly to the sensation: they plan to apply for mine 7 to be listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and to turn the mine into a museum so that the sensational find can be permanently displayed to the public.

Inconspicuous at first glance, but a sensation for geologists:

Traces of a Pantodon in mine 7.

The pantodon, a mammal from the Palaeogene (early Tertiary), the coal age of central Spitsbergen, is the oldest evidence of a mammal in this part of the Arctic. Remains of tree trunks, roots and branches can also be seen in the area.

Weave of branches and roots in mine 7.

So mine 7 has a future beyond this summer that everyone, including opponents of coal mining, can look forward to.

Fossilised tree trunk from the Palaeogene era.

News-Listing live generated at 2025/April/11 at 05:13:49 Uhr (GMT+1)